ITHACA, NY (CortacaToday) – The Wilder Brain Collection at Cornell University is magnificent, disorienting and mind-boggling, dating back to 1889. It is many things, but it is nothing short of awe-inspiring and thought-provoking.

Our brains are not unique to other animals. We all have two hemispheres, a cerebellum, a brain stem, and the major connections that you would find in our brain are present in say a fish or a bird.

So, what is it that makes us unique? This is the question that has long challenged anatomists like Wilder and continues to challenge the neuroscientists of today. Collection curator Timothy J. DeVoogd, professor in psychology and neuroscience at Cornell University, met to discuss this and more.

The collection was started in the 19th century by Burt Green Wilder (1841-1925), a Cornell faculty member and professor of comparative anatomy and zoology that pioneered the use of brain measurements for education. His work greatly influenced neuroscience education and marks a historical turning point in the understanding of human biology.

His goal in starting the collection was to examine any detectable differences between the brains of educated and uneducated people, genders, races and ethnicities, and those with mental illnesses and those without. The method at the time was to physically look at the brains of the deceased, whereas today we have access to brain-imaging technology.

Wilder’s research disproved any biological basis for claiming inferiority due to sex or race. In his  time, there was a common belief that the smaller average size of women’s brains was substantial enough evidence declare their intellect was inferior to men’s. Wilder’s studies established that there were no meaningful differences among the brains people of different genders, races, or education levels. Furthermore, he found that when proportion to body size was taken into account, men did not on average have larger brains, “with respect to body size, it flipped because men typically have larger bodies than women, heavier bodies than women, and so then the women’s brains were slightly, a percent bigger than men’s brains, and so there was no data then supporting that point of view,” DeVoogd said. Still, many at the time dismissed Wilder’s studies and continued to make ungrounded claims about differences among races and sexes. Thus, Wilder used his work for education and outreach to counter those claims that brain measurements could be used assert superiority of one race or sex.

time, there was a common belief that the smaller average size of women’s brains was substantial enough evidence declare their intellect was inferior to men’s. Wilder’s studies established that there were no meaningful differences among the brains people of different genders, races, or education levels. Furthermore, he found that when proportion to body size was taken into account, men did not on average have larger brains, “with respect to body size, it flipped because men typically have larger bodies than women, heavier bodies than women, and so then the women’s brains were slightly, a percent bigger than men’s brains, and so there was no data then supporting that point of view,” DeVoogd said. Still, many at the time dismissed Wilder’s studies and continued to make ungrounded claims about differences among races and sexes. Thus, Wilder used his work for education and outreach to counter those claims that brain measurements could be used assert superiority of one race or sex.

Although we can now look at the brains of the living non-invasively, his collection continues to be invaluable—for the generally curious, the sake of fascination, and the necessity to look into the past to see where the future can take us.

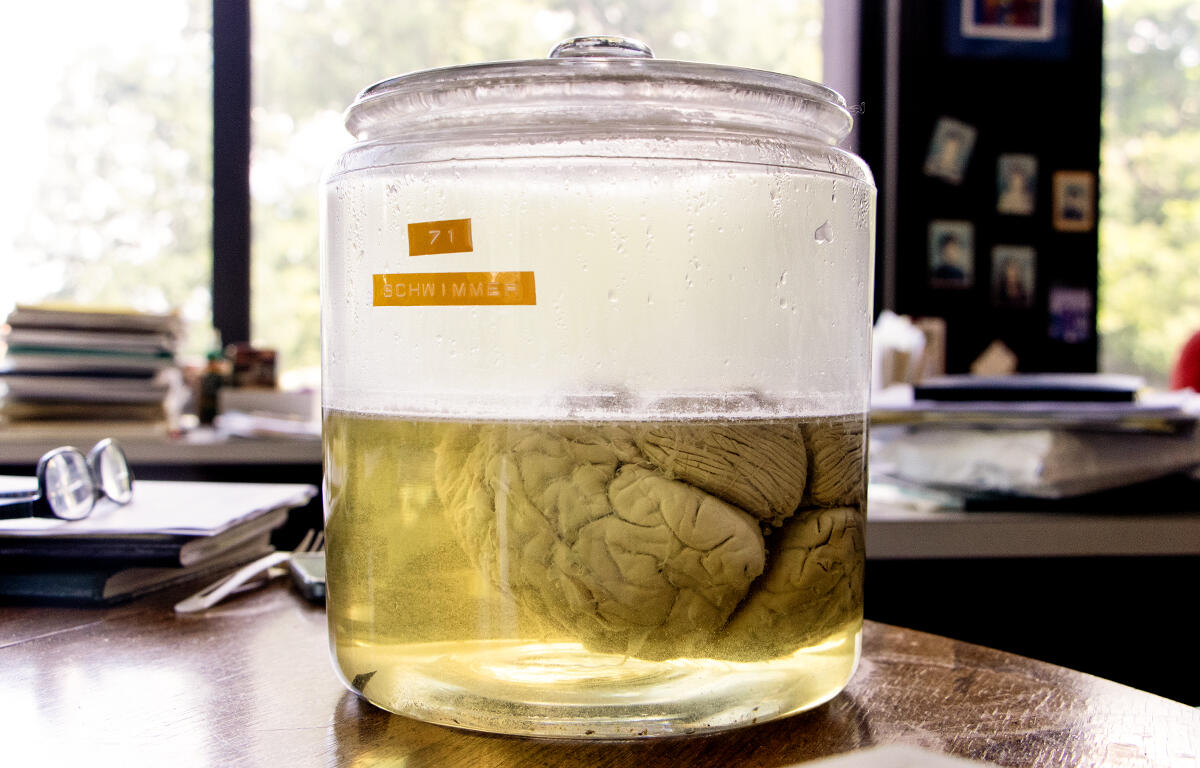

“The purpose [the collection] it serves now is to get people thinking about how their own brains work. Students often come by and stand out there. Families that are showing their kids around campus come and stand by. Fairly often, if I’m not busy with something, I’ll start talking to them and I think little kids in particular get fascinated and come up with all kinds of neat questions,” DeVoogd said. DeVoogd keeps one brain from the collection is his office, Rosika Schwimmer’s. Who was she and how did her brain get here?

“The purpose [the collection] it serves now is to get people thinking about how their own brains work. Students often come by and stand out there. Families that are showing their kids around campus come and stand by. Fairly often, if I’m not busy with something, I’ll start talking to them and I think little kids in particular get fascinated and come up with all kinds of neat questions,” DeVoogd said. DeVoogd keeps one brain from the collection is his office, Rosika Schwimmer’s. Who was she and how did her brain get here?

• Idealist and activist, Rosika Schwimmer‘s (1877-1948) brain out of all the brains on display is the only one that has no direct affiliation with the university, Wilder, or Ithaca. Schwimmer was a Hungarian-born writer, political activist, feminist, and pacifist. Most notably she organized with famous suffragist and political activist Carrie Chapman Catt’s, who won Woodrow Wilson’s support in campaigning for the 19th amendment. The two lectured across the United States on women a suffrage and the human cost of war. Catt arranged an audience with Wilson for Schwimmer to convince him to act as a neutral mediator in World War I, but the meeting was unsuccessful in swaying him. Nonetheless, she persisted and won Henry Ford’s backing in her campaign for peace. She worked tirelessly her whole life for progress and to put an end to warring between nations. Perhaps to some, her views were idealistic—campaigning for a World Government, dissatisfied with what was then the League of Nations (United Nations), believing the only way to prevent war was through global legislation. She asked that her brain be donated to the collection, perhaps so her mission of pursuing progress would endure long after she was gone.

Originally, the collection had hundreds of brains with corresponding numbers to help identify who they belonged to, but these records were lost in the ’70s when the curator at the time faced declining health and was unable to properly preserve the brains, leading to hundreds drying out and being left unidentifiable. Still, there are nine that were maintained and still are on display in Uris Hall. Others that were preserved, “about 20 or 30,” DeVoogd said, but had no record of who they belonged to live in the basement of Uris Hall as curiosity for professors and students.

Who else is “in” the collection?

• Ithaca’s famed scholar and murderer Edward Rulloff’s brain was preserved and then acquired by Wilder for his collection—though the details of this transaction are unclear. Rulloff was linked to several murders, including the killing of his wife, Harriett Rulloff, and their infant daughter in 1845. Due to lack of evidence, he managed to avoid conviction for these murders. He was later convicted and jailed for several other crimes, including the murder of a store clerk in Binghamton, New York, which led to his execution, a public hanging.

• Former Cornell professor and suffragist, Helen H. Gardener, who you can read more about here. She left a legacy as a pioneering woman in the top ranks of the U.S. federal government.

Neuroscience has come a long way since Wilder’s studies. We now know that who we are is ultimately determined by connections made in our brains, those that have endured from our ancestors, and those that are new and uniquely formed from our own experiences.

“We have one hundred billion nerve cells in our heads, and it’s the connections and interactions between those cells that determine who we are …. Some of those connections may go awry in people that are psychopaths, but most people aren’t psychopaths. And so, what is there that makes your brain different from mine? Well, patterns, or general patterns of connection that are different because of our genes and our early experience, and beyond that, patterns that we create by what we learn and what we do,” said DeVoogd.

The missing link is we can’t pinpoint and map out where those individual differences are—where one’s formative memories lie, the exact connection that results in someone’s optimism or another person’s pragmatism: “If we talk to each other, we start to know what the differences are, but we don’t really, really understand where they come from.” Neuroscientists can’t look at a brain scan and tell what someone was seeing, hearing or thinking in the scanner, but there is still a lot we can see from brain-imaging technology, like a couple in love’s synchronization and social connectedness or the regions of the brain where the emotion manifests itself.

Gradually scientists are attempting to find ways around existing barriers to translate internal experiences into words using brain imaging. DeVoogd shared that theoretically, the brains in the collection that have been preserved still contain the memories—the neural pathways—of the person who lived, and that if there was some way to encode those connections, we could understand the world through Rosika Schwimmer’s mind and really see what it is that drove her to activism, “If you were able to work out all the connections that are present, it would be Rosika Schwimmer. It would be her memories, it would be her emotions, it would be her way of approaching things … It’s still there. I mean, she died, what, 80 years ago, but we are biology… Maybe not ever, but at least theoretically, you could go in there and find who she was,” DeVoogd said.

That would certainly put a new spin on things, just thinking about a whole world that exists in one mind can shift perspectives. The work is never done, and the mystery of what makes us the similar and different, the same as Wilder’s original intentions for the collection, continues to make us use our brains and think: what are we really?